Let's Make A Deal

|

The particular game that we are concerned with here is where Monty Hall offers you the opportunity to win what is behind one of three doors. Typically there was a really nice prize (ie. a car) behind one of the doors and a not-so-nice prize (ie. a goat) behind the other two. After selecting a door, Monty would then proceed to open one of the doors you didn't select. It is important to note here that Monty would NOT open the door that concealed the car. At this point, he would then ask you if you wanted to switch to the other door before revealing what you had won.

The Controversy

|

In September of 1991 a reader of Marilyn Vos Savant's Sunday Parade column wrote in and asked the following question:

"Suppose you're on a game show, and you're given the choice of three doors: Behind one door is a car; behind the others, goats. You pick a door, say No. 1, and the host, who knows what's behind the other doors, opens another door, say No. 3, which has a goat. He then says to you, 'Do you want to pick door No. 2?' Is it to your advantage to take the switch?"

This problem was given the name The Monty Hall Paradox in honor of the long time host of the television game show "Let's Make a Deal." Articles about the controversy appeared in the New York Times and other papers around the country. Marilyn's answer was that the contestant should switch doors and she received nearly 10,000 responses from readers, most of them disagreeing with her. Several were from mathematicians and scientists whose responses ranged from hostility to disappointment at the nation's lack of mathematical skills.

This question seems to have a non-intuitive answer. Why were so many convinced that Marilyn Vos Savant was wrong? They had all decided that it did not matter if the contestant switched or did not switch. There may be a reason so many disagreed with her. Omitting one phrase in the statement of this problem changes the answer completely and this might explain why many people have the wrong intuition about the solution. If the host (Monty Hall) does not know where the car is behind the other two doors, then the answer to the question is "IT DOESN'T MATTER IF THE CONTESTANT SWITCHES." The change in the statement of the problem is so slight that this might be the reason this problem is such a "paradox."

To Switch or Not To Switch

Well, looking at the numbers, it would appear that those who switched doors won about 2/3 of the time and those who didn't switch won about 1/3 of the time. Why is there such a large difference? I mean, once Monty shows you what's behind one of the doors, there are only two doors left. Right? Right. And the car is behind one of those two doors with equal probability. Right? WRONG!

|

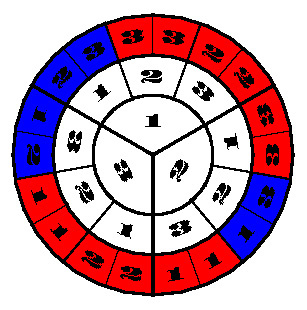

To analyze this problem we represent this senario as a random variable on a roulette wheel. The roulette wheel on the left simulates the Let's Make a Deal game. The inner wheel represents the number of the door that the car is behind, the middle wheel represents the door that is selected by the contestant, and the outer wheel represents the door Monty Hall can show. Spinning this roulette wheel once is equivalent to playing the game once. The outer wheel also tells you what your strategy should be to win. The red means that in order to win the contestant needs to switch doors, and the blue means that the contestant should not switch. Notice that there are twice as many red sections as blue. In other words, you are twice as likely to win if you switch than if you don't switch! What this wheel makes evident is that with probability 1/3 the contestant selects the correct door in which case it would be better not to switch. In the other 2/3 of the cases, Monty Hall is telling the contestant where the car is! |

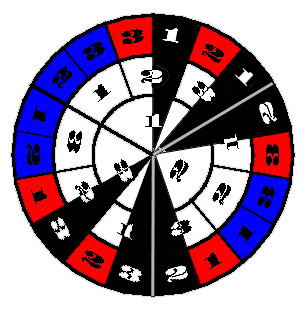

| If this is the senario then the wheel looks almost the same, the inner wheel represents the door that the car is behind, the middle wheel represents the number of the door that is selected by the contestant, and the outer wheel represents the door number Monty Hall will show the contestant. This time however, Monty Hall has the option of opening a door with a car behind it, but by chance he didn't. Playing the game under these assumptions is equivalent to spinning the roulette wheel to the right except that if the blackened area of the wheel comes up then it is spun again. Once again the red area means that in order to win the contestant will need to switch doors, and the blue means that the contestant should not switch. Notice that there is the same amount of red area as blue. In other words, it doesn't matter if the contestant switches in this case. |

|

Why aren't the numbers coming out exactly 2/3 and 1/3?

Okay, so this wouldn't be covered in this class, but since you might be wondering and since it doesn't take much to explain.... Let's start by looking at a different example: flipping a coin. If you were to flip a coin 100 times, you would expect to get 50 heads. Would you think twice though if afterwards you counted 53 heads? How about 47 heads? Probably not. Well, this is the basic idea behind a confidence interval, to come up with a range of acceptable values for your outcome, instead of a single expected value.In the table below are listed confidence intervals for several different number of players. In this case, they are 95% confidence intervals, which means that 95% of the time, the outcome should fall within the interval. In other words, only 1 time out of 20 trials should the outcome NOT fall within the specified interval. For instance, say that you played Let's Make a Deal nine times and switched every single time. Then you would expect to win 6 times, but would not be surprised if you won anywhere from 3 to 9 times. Say you repeated this twenty times and kept track of the number of times you won out of 9 trials. On average, you would win about 6 times, with most of your values being in the confidence interval and maybe 1 value outside the interval.

| If All Players Switched | If No Players Switched | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| # of Players | 95% Confidence Interval | Expected Value | 95% Confidence Interval | Expected Value |

| 9 | 3-9 | 6 | 0-5 | 3 |

| 51 | 27-40 | 34 | 10-23 | 17 |

| 99 | 57-75 | 66 | 24-42 | 33 |

| 150 | 88-111 | 100 | 38-61 | 50 |

| 201 | 120-146 | 134 | 54-80 | 67 |

| 249 | 151-180 | 166 | 68-97 | 83 |

| 300 | 183-215 | 200 | 83-115 | 100 |

| 399 | 246-283 | 266 | 115-152 | 133 |

| 501 | 313-354 | 334 | 146-187 | 167 |

| 999 | 636-694 | 666 | 304-362 | 333 |